A taste of New Orleans, with a side of history

When you come from NOLA, North Park's Preston Bax III says, "everybody is hungry and has something to prove." Coach Sean Smith calls it "being crazy in a good way."

North Park junior guard Preston Bax III won a Louisiana state championship while at St. Augustine, a legendary high school in New Orleans. His relentless style of play has found a new home with the Vikings.

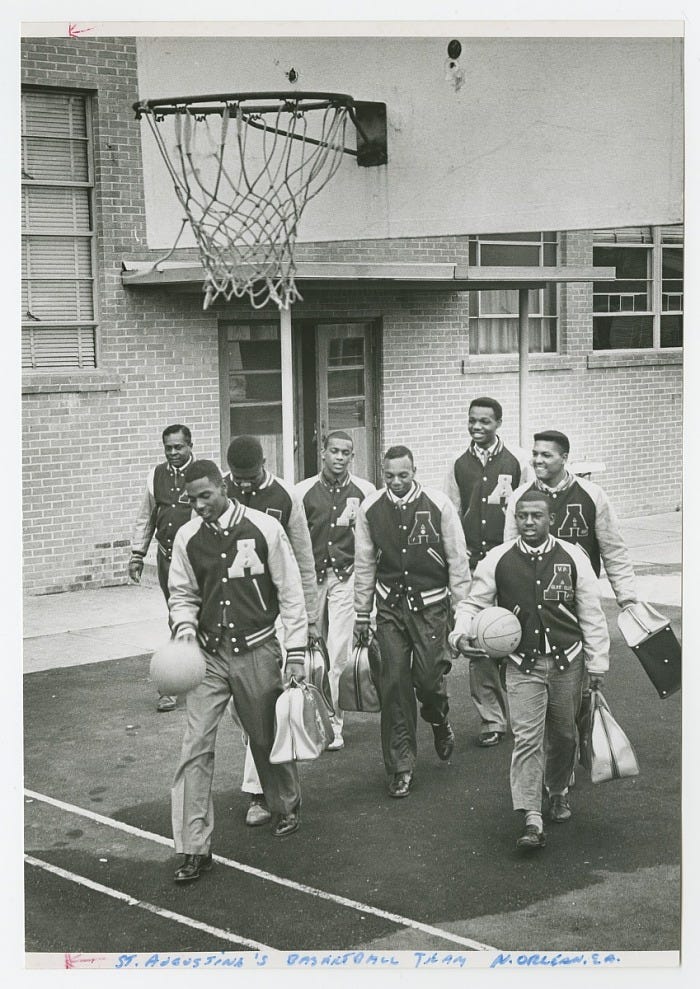

The black-and-white newspaper photograph, nearly 60 years old now, can be found in the Smithsonian, in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. It shows eight young Black basketball players from New Orleans wearing matching letter jackets, a large A stitched over their hearts.

Two players are carrying basketballs. Five are carrying matching gym bags. They all played for the Purple Knights of St. Augustine, an all-black high school, and what they did—taking the court on Feb. 25, 1965 against an all-white team, Jesuit High, in a game played in a shroud of secrecy in segregated Louisiana--was world-changing.

This St. Augustine High School basketball team has a place in the same civil rights narrative as Rosa Parks and the Woolworth’s sit-in. [Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of St. Augustine High School, New Orleans, LA]

“The history of my school,’’ said North Park guard Preston Bax III, a child of New Orleans and a graduate of St. Augustine, “runs deep.’’

Those teenagers of St. Augustine belong in the same narrative as a brave Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat for a white passenger on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, or the students from Tougaloo staging a sit-in at a lunch counter in Woolworth’s in Jackson, Mississippi.

The Smithsonian obviously thought so. And so did Hollywood, which made a movie (“Passing Glory”) about the game written and produced by the actor Harold Sylvester, who played on that St. Augustine team, and starred Andre Braugher, the brilliant actor (“Glory,”“Homicide: Life on the Street,” and “Brooklyn Nine-Nine”) who just died of lung cancer two weeks ago.

The principals of the two schools, determined to prove that black and white could play on the same court even as previous efforts to integrate had failed, quietly arranged for the schools to meet in what was essentially a scrimmage. Jesuit was the champion of the city’s all-white Catholic League. St. Aug, as it was known, was champion of the Louisiana Interscholastic Athletic and Literary Organization, in which the state’s black schools competed. The coaches took care of the details.

There was little discussion about where the game would be played: in Jesuit’s gym, on Carrollton Avenue.

“We didn’t have a gym,’’ Sylvester said in an interview with New Orleans public radio station WWNO. “We didn’t have lockers, we didn’t have a shower. And so, walking into that gym for the first time was like, ‘Wow, what is this?’”

Some parents, especially those of the St. Aug players, had reservations about allowing their kids to play. Just days before, Malcolm X had been assassinated.

“That same year,’’ Sylvester recalled in that radio interview, “we went up to Bogalusa and we had a new priest from the north who came down and wanted to stop for some pie. We tried to tell him that we couldn’t stop in that place, but he really didn’t understand.

“…There were four of us that went into that restaurant and they just ignored us. But the next thing we know, trucks started pulling up to the front of the restaurant, and the guys literally came in and dragged us out and took us to the back of the building. And this, in my memory--and this is an indelible memory--is the shotgun that got pressed to my forehead. So, that happened. And so now, two months later, three months later, we have a proposition about going into Jesuit knowing what can happen and what often happened at that time.”

The game was played before a handful of family members and faculty, Sylvester said. A Jesuit player told the radio station that score was not kept; Sylvester said St. Aug won by 22. It would be months before the city’s newspapers learned of the game, but the impact would be profound: Within a year, a lawsuit brought by St. Augustine prevailed, integrating high school sports in Louisiana. Sylvester would become the first black player to be given a basketball scholarship by Tulane University.

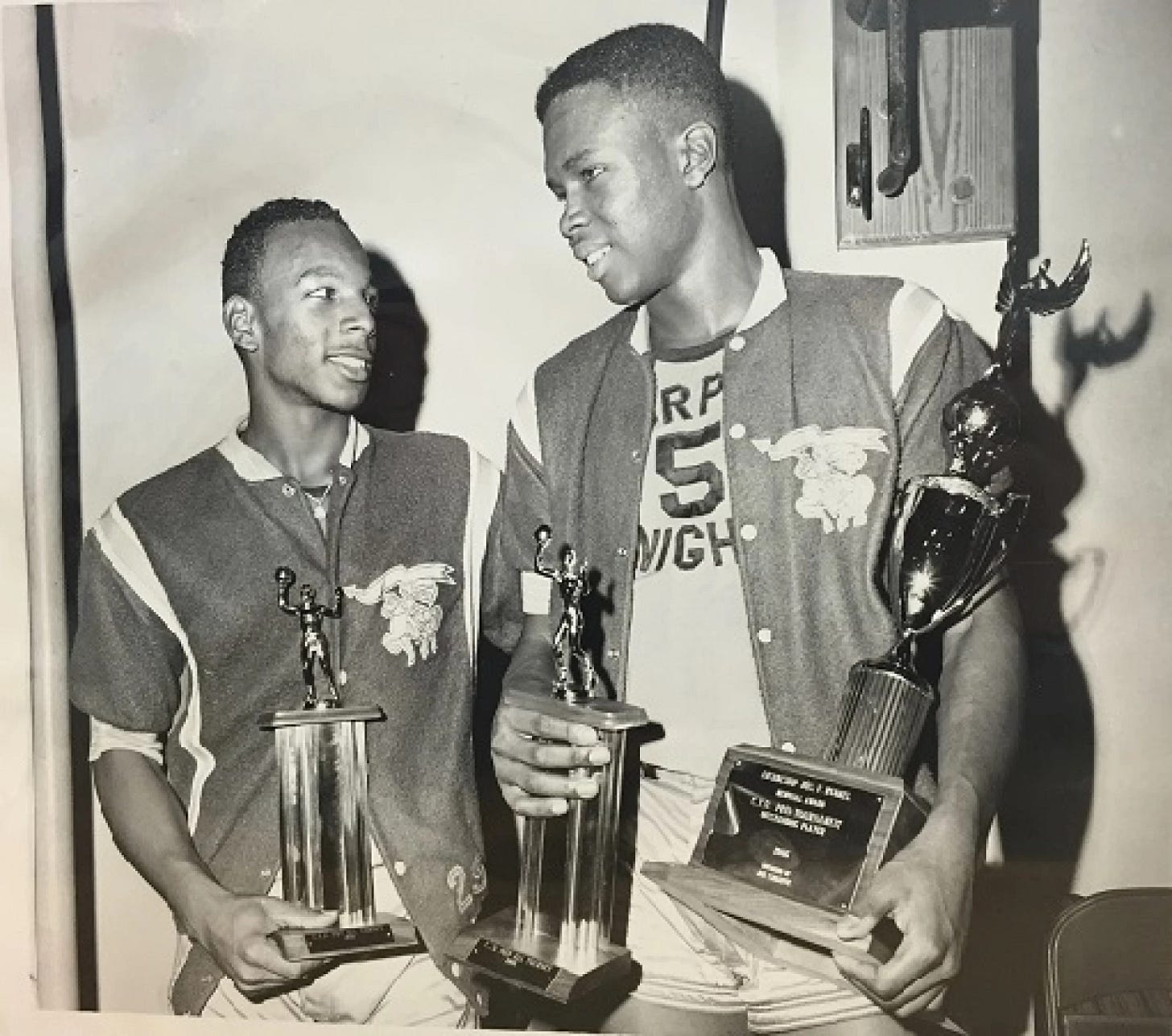

Harold Sylvester (right), who went on to become an actor and producer, starred for the St. Augustine High team that paved the way for Louisiana high school sports to be integrated. He made the film, “Passing Glory,” about the Purple Knights. [Credit Harold Sylvester / Amistad Research Center]

St. Augustine is integrated now, though it remains the leading secondary school for black males in the state of Louisiana. The list of notable alumni produced by the school is impressive. It includes Sidney Barthelemy, the second Black to be elected mayor of New Orleans; Dean Baquet, former executive editor of the New York Times; Grammy Award-winning musician Jon Batiste; actor Carl Weathers, who played Apollo Creed in the “Rocky” movies; mathematician Percy A. Pierre, who at one point served as the acting Secretary of the Army; ESPN sportscaster Stan Verrett; and a host of athletes who played in the NFL or NBA, including running back Leonard Fournette (Tampa Bay, Jacksonville) and former point guard, NBA and college coach, and broadcasting analyst Avery Johnson.

It is a source of pride for Bax III, who was a senior point guard in 2021 when St. Augustine won the state Division I championship over Scotlandville, the team that had knocked out Jesuit in the semifinals that season and had beaten the Purple Knights in the finals in each of the previous two years. This was the sixth state title won by St. Aug since integration, the first since 2011.

“Just being in that program,’’ Bax III said, “being part of all the hard work, dedication, determination and sacrifice helped build me up and prepare me for college ball.

“Just coming from New Orleans, everybody’s just hungry and got something to prove.’’

For a time, it was no sure thing that Bax III would be able to go to St. Augustine. The school sustained millions of dollars worth of damage from Hurricane Katrina; Preston and his family left the city before the hurricane hit, severely damaging their home; they fled to Atlanta, where his grandfather worked as a bus driver and owned a home. It would be more than a year, Preston said, before his family was able to return to New Orleans, and the high school rebuilt and reopened its doors.

Bax III initially thought his future was as a football player. His younger brother, Jonathan, was the basketball player. But then the brothers flipped. Jonathan just completed his freshman season as a linebacker at Texas Tech, while Preston became a point guard. He played little as a sophomore and junior at St. Augustine, and while he blossomed his senior season, he did not receive the attention from college recruiters that many of his teammates did. He wound up choosing to play at Houghton University in upstate New York.

“I had a really good freshman year and was planning to return,’’ he said, “but then my coach got fired.’’

Bax III decided it was time to move on. How he ended up at North Park is a story in itself. The coach who recruited him to Houghton, Kendall Aldridge, took an assistant’s job at Division II Purdue Northwest, which is coached by Boomer Roberts, Sean Smith’s old college coach at Trinity University. Aldridge recommended Bax III take a look at North Park; Smith and associate coach Edwind McGhee did the rest.

“The crazy part,’’ Bax said, “is my parents didn’t want me to go back out, so far away from home. I was the first person in my family to travel outside of Louisiana to go to college.’’

Yes, Bax III said, there were times he felt homesick. “But then you just find the ones who are around you,’’ he said, “and build a relationship with them. That’s why I love this program so much. They not only gave me the opportunity to play the game I love, but it gave me friendships and a family that I can never break. I’m really thankful to God for this opportunity.’’

Bax III played sparingly in his first season with North Park. He admitted that while he passed both semesters, there were times his effort flagged in the classroom, which didn’t escape Smith’s attention.

“In a way, I think that showed me I needed to grow up, and grow up fast,’’ Bax III said. “I think that’s what college is all about, just growing and learning from your mistakes.

“I grew as a person, not just as a person but as a young Black man. I come out here, I’m not just playing for myself, I represent my family, I represent my city, I represent everything, you know.’’

This season, the minutes (about 13 a game) have come for Bax III, who is listed at 6-foot-3, 185 pounds. So have the starts, as Smith has searched for the right combination of players during the team’s early struggles. He has started four games, including the last three. He made all three of his shots in Friday’s 73-53 romp over overmatched Alfred (N.Y.) University in the Music City Classic in Gallatin, Tenn. Saturday’s game against Central College (Iowa) will be a much sterner test.

But it is his ceaseless energy on defense—St. Aug played the same kind of full-court pressing style that North Park does—that earns Bax III his playing time.

“Every practice, every game, he’s the catalyst,’’ said Shamar Pumphrey, North Park’s all-CCIW senior point guard, after North Park’s most impressive win of the season, a 75-63 takedown of highly regarded Hope College last week in which Bax III made his presence felt for 17 minutes—6 points, 4 assists, a steal and a rebound, in addition to his stifling defense.

“We look for that from him,’’ Pumphrey said. “Whether he comes off the bench or starts, we know Preston is going to bring that energy. I commend him every time I play with him because he makes me want to go harder.’’

Smith calls Bax III “the ultimate teammate.”

“He’s gonna push you,’’ he said. “He’s taken a big step from last year in terms of his voice and leadership. He’s definitely a spark for us.

“He’s crazy in a good way.’’

The New Orleans way. The St. Aug way.